If you follow the news, you might think the rental crisis in B.C. is easing. Recent headlines paint an optimistic picture:

B.C. rents continue downward trend, down nearly six per cent: Report (Vancouver Sun, November 7, 2025)

Renting? Report says Canada is at ‘best levels of affordability’ in 2 years (Global News, October 7, 2025)

Headlines like these could lead decision-makers to conclude that the worst is behind us and that it is time to scale back programs that support renters. But that would be the wrong conclusion at the worst time — and the consequences for hundreds of thousands of B.C. renters could be severe.

In this edition of Insights, we take a closer look at what is actually happening with rents in B.C. and why the data behind these headlines tells a very different story than the one making the news.

What the headlines are actually measuring

The rent trends described in recent media coverage are based on data from Rentals.ca, an online platform where landlords post ads to find tenants for vacant or soon-to-be-vacant homes. The company averages the asking rents in these ads to produce monthly statistics.1

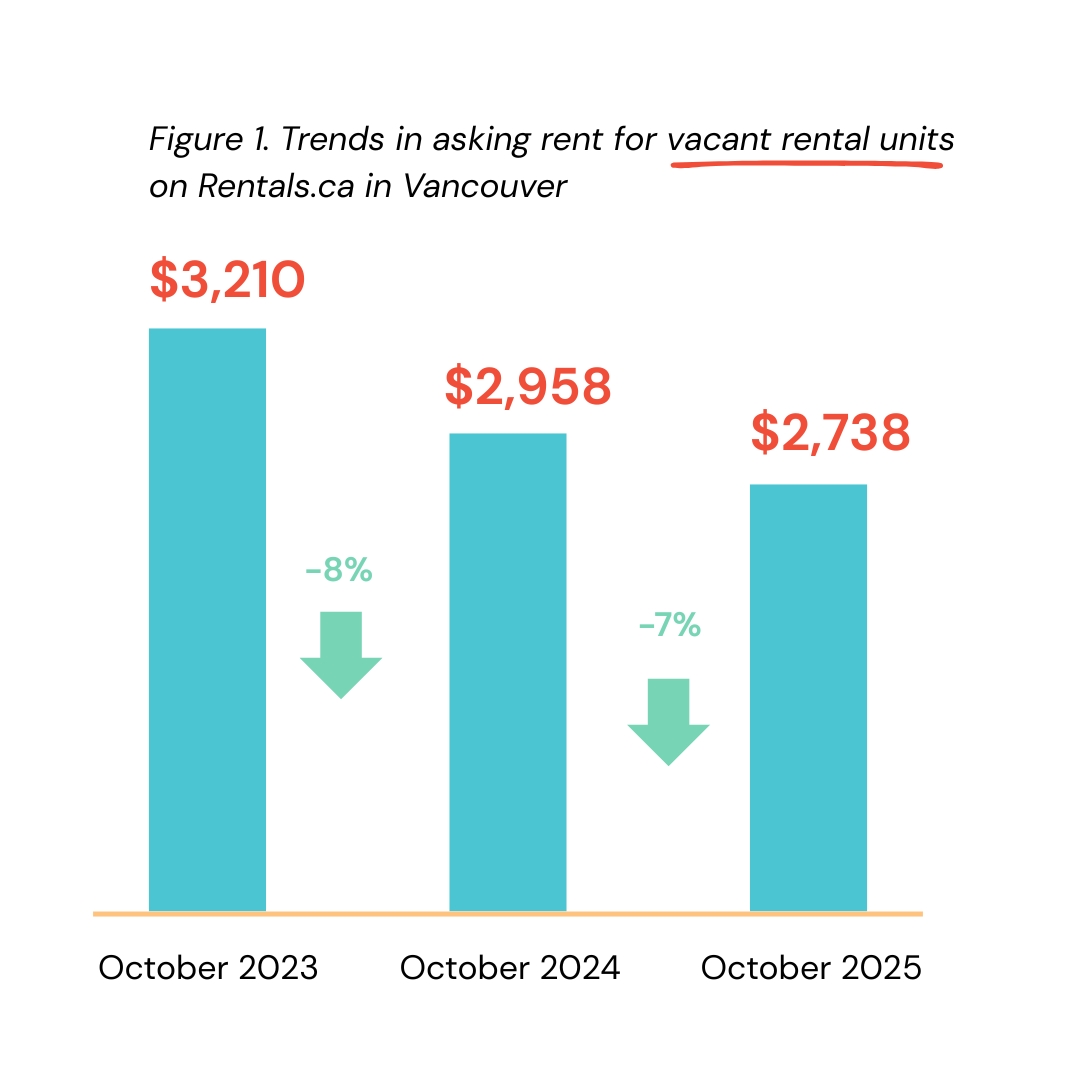

As shown in Figure 1, asking rents for these vacant units have indeed declined, falling from an average of $3,210 per month in October 2023 to $2,738 per month in October 2025.

This is indeed good news — but only if you are actively searching for a new rental, and only if you can afford to rent at the higher end of the market. These figures do not reflect what the vast majority of renters in B.C. are actually paying.

And even among those who are searching, the benefit depends on what you can afford. As we will show later in this piece, the decline in asking rents is concentrated in newer, higher-priced buildings — the same buildings where vacancy rates are six times higher than in lower-cost rentals. For people searching at the lower end of the market, where most renters are looking, competition remains fierce and options are extremely limited.

That said, any easing in the rental market is welcome. Government policies that have increased housing supply, reduced speculation and added protections for renters have likely contributed to this shift, and that progress is worth recognizing. But it would be a mistake to look at declining rents at the top of the market and conclude that the crisis is easing for renters across the board.

What renters are experiencing

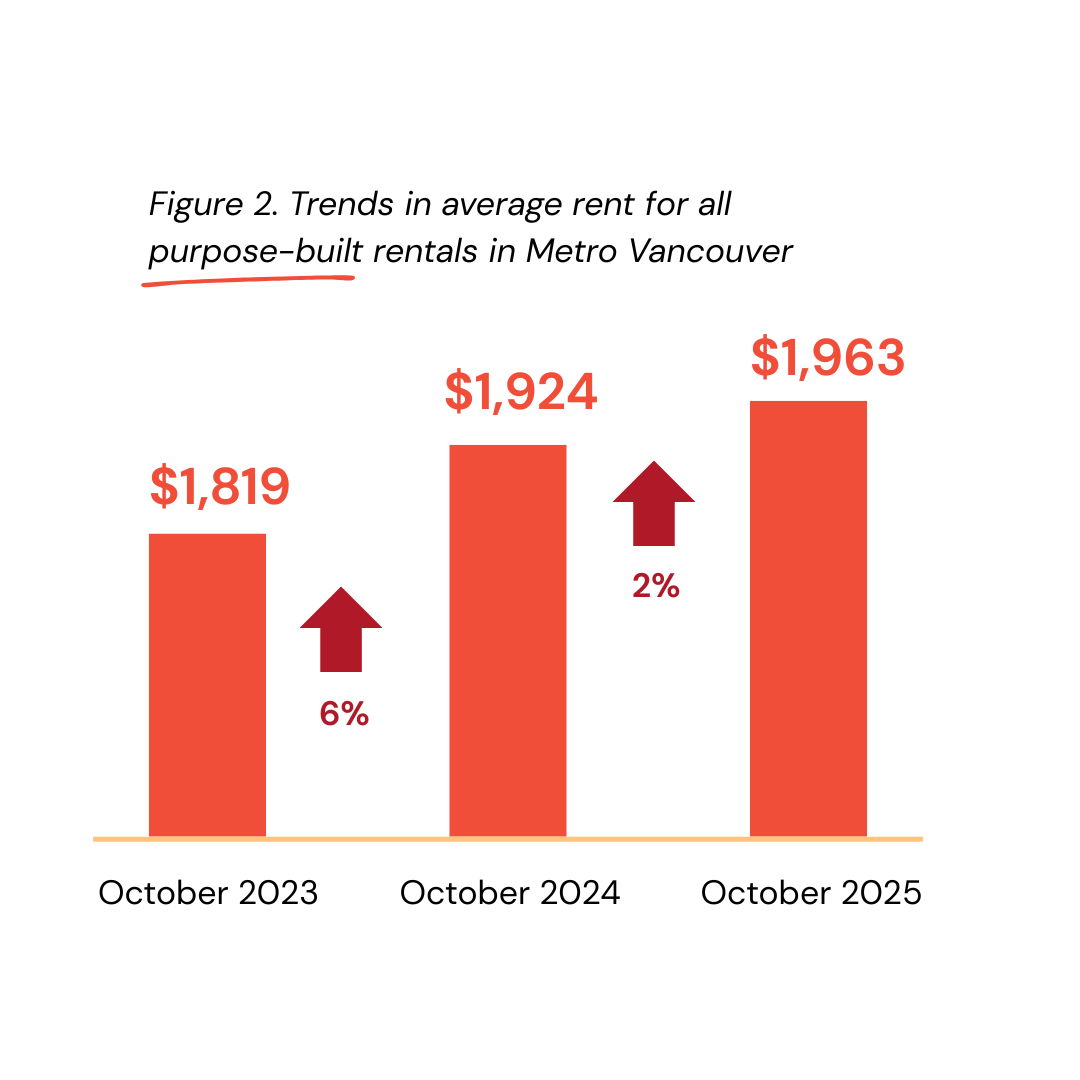

When we look at data that captures overall rents — what people across B.C. are actually paying each month — the picture is very different. According to the CMHC Rental Market Survey released in December 2025, average rents are still rising.

The Consumer Price Index confirms this: rental costs increased by 2.3% last year across all types of rental situations in B.C. That rate is still nearly double the average annual rent inflation experienced between 2010 and 2018 (1.6% per year).

And the provincial average masks even steeper increases in many communities outside of Metro Vancouver, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Differences in rent inflation by location (October 2024 to October 2025)

|

Average rent increase |

Location |

|

2.5 - 5% |

Penticton, Quesnel |

|

6 - 10% |

Nanaimo, Campbell River, Chilliwack, Summerland, Fort St. John, Victoria, Dawson Creek, Kelowna, Kamloops, Cranbrook |

|

Above 10% |

Williams Lake, Parksville, Duncan, Salmon Arm, Vernon, Prince George |

A closer look at Metro Vancouver

To understand what is driving these trends, it helps to look more closely at Metro Vancouver — the largest rental market in the province and the one with the most detailed data available.

Metro Vancouver is home to approximately2 360,000 households renting in the private market. Between 2024 and 2025, average rents increased by 2% for purpose-built rentals. That doesn’t sound too bad, but the details reveal just how challenging things are depending on the situation.

If a household did not move, their rent went up modestly — limited to the allowable annual increase set by the provincial government. But anyone who had to move faced a much bigger hit: on average $6,750 more per year for a newly built home, and $5,630 more for a previously occupied one.

Table 2. Rental units and changes to average rents in the private market (October 2024 to October 2025)

|

Tenants stay in units |

New tenants in units |

Brand new rentals |

|||

|

Rental units |

Change in monthly rent |

Rental units |

Change in monthly rent |

Rental units |

Change in monthly rent |

|

311,700 |

+ $44 |

40,900 |

+$470 |

2,900 |

+$640 |

Meanwhile, condominium apartments continue to be the number one source of new rental supply in the region, providing two-thirds of new units. Since 2024, there has been a net increase of 5,582 condo rentals versus 2,882 purpose-built rental homes – and condos rent for 38% more on average.

Even the average rent in a new purpose-built rental — $2,561 per month — is beyond the reach of most renters. At this level, rent is unaffordable for 70% of renter households (using the widely accepted benchmark that rent should be no more than 30% of income).

For asking rents on Rentals.ca to become affordable to even half of renter households in the region, they would need to fall three times further than they already have.

High rents are leaving homes empty while families search for affordable options

Something else striking is happening in the rental market. Some landlords of new buildings are releasing units gradually — floor by floor or one building phase at a time — rather than making them all available at once. In Burnaby alone, 31% of one-bedroom and 24% of two-bedroom rentals built since July 2022 are sitting vacant.

Across Metro Vancouver, vacancy rates are six times higher for the most expensive rentals compared with lower-cost homes. Renters looking for reasonably priced homes face a very tight market with fierce competition for limited options.

Families often face added challenges. For households in the lowest-income quartile looking for a two-bedroom home, the vacancy rate is just 0.5% — making it next to impossible to find something affordable.

New supply is not reaching the people who need it most

In Metro Vancouver, there are more than 100,000 households in core housing need — roughly one in three renter households. Last year, approximately 1,400 new non-market rental homes opened across the region. That is enough to serve about 1% of these households.

The remaining 99% of renter households in core housing need will not benefit from recent increases in rental supply. And none will benefit from declining asking rents on Rentals.ca — because those rents are still far above what they can afford.

Now, some argue that building any new housing — even at the higher end — eventually benefits lower-income renters through a process economists call "filtering," where new supply frees up more affordable homes down the chain. While there may be some truth to this over the long term, it is a slow process3 that depends on sustained, stable market conditions.4 For renters who are in crisis now, filtering cannot happen fast enough and it is easily disrupted by the kind of population growth, economic shocks and supply constraints that B.C. has faced – and continues to experience.

The growing gap between wages and rents

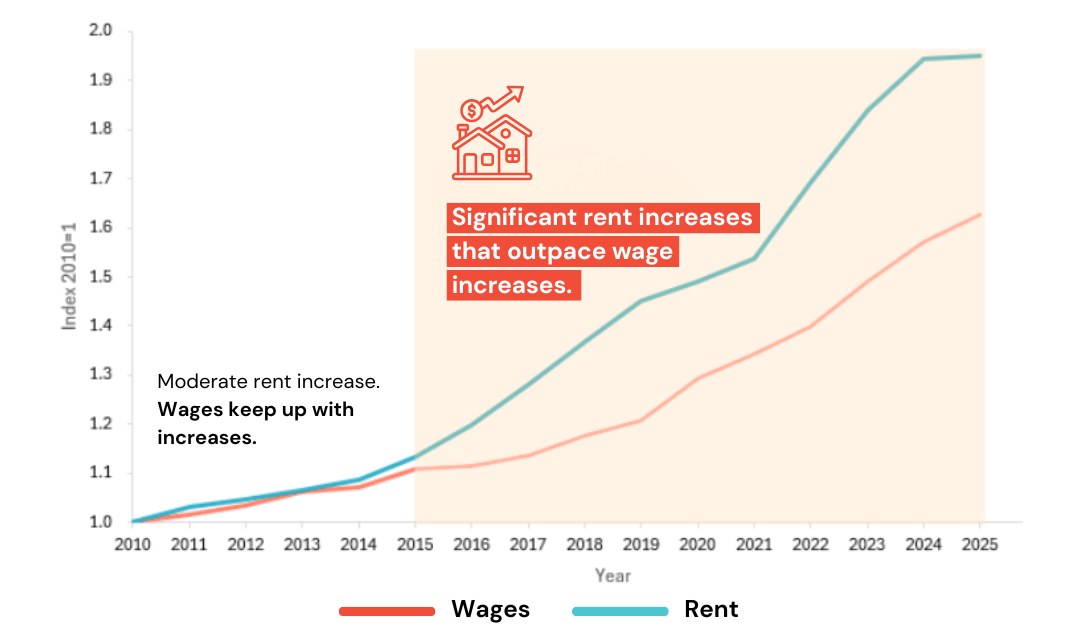

Beyond the mismatch in new housing supply, there is a widening gap between incomes and rents. Until recently, wage increases in B.C. roughly kept pace with rent increases. But since 2015, that relationship has shifted dramatically.5

The result is a significant increase in housing insecurity across the province. This situation is particularly dire for the more than 100,000 households in B.C. with incomes below $50,000 per year who are paying more than half their income on shelter.

When rent takes up this much of a household’s budget, there is little left for other essentials. Many families turn to food banks for help with groceries. They have no savings to fall back on. And when an unforeseen crisis hits — a job loss, an injury, a family emergency — there is no buffer. The result, too often, is eviction.

The safety net that catches people before they fall

Evictions are not formally tracked in B.C., so it is impossible to know exactly how many people have lost their homes because they could not pay rent. But we do know that since 2021, more than 25,000 households have contacted BC Rent Bank in a housing crisis.

BC Rent Bank provides emergency financial assistance to help renters avoid eviction, gain access to housing, prevent utility disconnection and stay housed during an unexpected crisis. Across 19 community rent banks in every region of the province, the program has helped more than 15,000 people since 2019. 91% of renters who received support maintained their housing stability. Without that support, 66% would likely have faced being homeless.

The program also delivers significant cost savings. Every dollar invested in BC Rent Bank generates five dollars in savings for renters and the provincial government — through avoided costs for emergency shelters, health care, housing placement and children and youth placed in care. To date, BC Rent Bank has generated more than $150 million in public and private cost savings across the province.

At a time when demand for rent bank services continues to rise — with applications up 13% and financial support up 16% between 2024 and 2025 — this proven program needs sustained investment more than ever. Their current provincial funding agreement expires in spring 2026, and without renewed commitment from the provincial government, BC Rent Bank will not be able to continue operating. Loss of funding would dismantle the province-wide network and push vulnerable renters toward eviction at the very moment demand is highest.

Now is not the time to pull back

The data in this report makes one thing clear: the rental crisis in B.C. is far from over. Rents are still rising, the gap between incomes and housing costs continues to widen and new supply is not reaching the people who need it most.

While programs like BC Rent Bank help people stay housed during a crisis, we also need sustained investment in permanently affordable, community-owned housing — the kind of housing that is protected from market forces and directed to those who are currently struggling the most with housing costs. Both emergency supports and long-term solutions are needed. One without the other is not enough.

Declining asking rents on a listings website should not be mistaken for substantial progress on affordability. When the provincial government reveals its 2026 budget on February 17, it will have a choice: act on the evidence that renters across B.C. are still in crisis, or rely on misleading headlines to justify pulling back. Renewing funding for BC Rent Bank would be a clear signal that the government understands what the data actually shows — and that it stands with the thousands of renters who are one crisis away from losing their homes.

Key takeaways

-

Headlines about declining rents are based on asking rents for vacant homes listed on Rentals.ca. Overall rents in B.C. are still going up.

-

Renters who need to move face significantly higher costs: up to $7,680 more per year for a newly built home in Metro Vancouver. Rent is unaffordable for 70% of renter households even at average purpose-built rental rates.

-

98% of renter households in core housing need in Metro Vancouver will not benefit from recent increases in rental supply. We need significantly more non-market, community-owned housing.

-

Housing insecurity is increasing because of a widening gap between wages and rents. Emergency programs like BC Rent Bank are more critical than ever, and their provincial funding must be renewed before it expires this spring.

-

Declining asking rents on a listings website are not a sign that the crisis is over. Until rents come within reach of the people paying them, scaling back renter supports would be premature and harmful.

Sources

(1) Statistics Canada has recently developed Quarterly Rent Statistics that also pulls in data from other rental listing platforms as well.

(2) It is an estimate because there are no available data since 2021. This should improve after Census data is available for 2026. We do have reasonable updated data for purpose-built rentals, and rented-out condominiums but not for other parts of the secondary rental market and non-market housing.

(3) CMHC research finds that rents in a building typically decline by about 5% in the first four years and nearly 20% after 20 years. https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/professionals/housing-markets-data-and-research/housing-research/research-reports/accelerate-supply/understanding-filtering-long-term-strategy-new-supply-housing-affordability

(4) Research in Housing Policy Debate found that filtering varied significantly across time periods and market conditions, reversing entirely between 2015 and 2021. The study concluded that filtering "cannot always be relied upon as a source of affordable housing." Spader, J., "Has Housing Filtering Stalled? Heterogeneous Outcomes in the American Housing Survey, 1985–2021." https://nlihc.org/resource/new-study-examines-filtering-dynamics-us-housing-supply

(5) Sources: Statistics Canada: Table 14-10-0064-01 Employee wages by industry, annual; Statistics Canada. Table 34-10-0133-01 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Average rents for areas with a population of 10,000 and over. (Data in the figure are the average of the data for 7 communities that represent most renters in B.C.)